The Link Between Metaverse Coins and Virtual Real Estate Bubbles

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

2.1 Bubble Timestamping

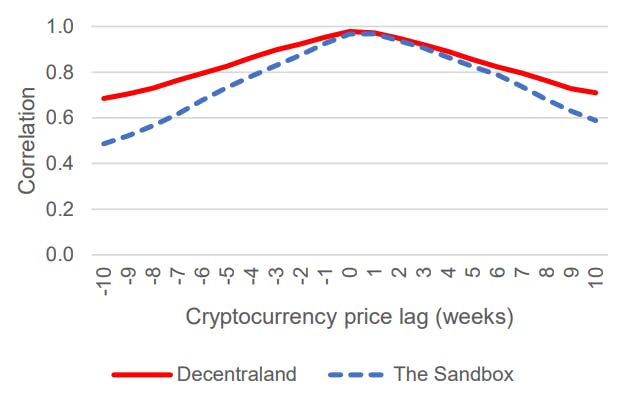

2.2 Cryptocurrency-LAND Wealth Effect

3. Results

3.1 Bubble Timestamping

3.2 Cryptocurrency-LAND Wealth Effect

3.3 Granger Causality Test

4. Conclusion and References

Appendix: Bored Ape Yacht Club’s Otherside

4. Conclusion

In this article, we document the wealth spillover effect from metaverse cryptocurrencies (MANA and SAND) into their corresponding virtual real estate (LAND NFTs). Real estate bubbles have occurred throughout history. In the case of these metaverses where opportunities to directly earn real estate income are not established, the situation reminisces the Florida real estate bubble in the mid-1920s. In an article discussing lessons from the 1920s crisis relevant to the 2008 crisis, White (2009) pointed to Galbraith’s (1954) observation that rather than being “elements of substance”, real estate prices were “based on the self-delusion that the Florida swamps would be wonderful residential real estate”.

While Simpson (1933) surmised that the 1920s American real estate bubble was a result of a “dangerous” collaboration between banks, real estate promoters and local politicians, rather than wealth spillover effect from other sources, it nevertheless provided the necessary ingredient for leveraged positions in equity during the late 1920s. Thus, it could be argued that wealth spillover had its role in the 1929 crash. From the analysis in White (2009), the real estate-equity double bubbles spanned almost a decade, but in the crypto world where price movements are more volatile and change more rapidly, the wealth effect can take just weeks (if not days, as suggested by the BAYC’s result in the Appendix) to occur. As evident from the 2008 crisis, evaporation of real estate wealth can cascade into a systemic crisis. For this metaverse cryptocurrency-LAND double bubble, the impact is likely limited as NFTs are not yet widely accepted as loan collateral, but our finding confirms that the fear outlined by the FSB is justified.[8]

Online communities often jest that the decentralized finance “experiment” is “speed running the evolution of the modern financial system”. [9] but put differently, it also means we are reliving our mistakes from the past, and some are paying the price for it.

REFERENCES

Barberis, N. (2018). Psychology-based models of asset prices and trading volume. In Handbook of behavioral economics: applications and foundations 1 (Vol. 1, pp. 79-175). North-Holland.

Baur, D. G., & Dimpfl, T. (2018). Asymmetric volatility in cryptocurrencies. Economics Letters, 173, 148- 151.

Bouri, E., Gupta, R., & Roubaud, D. (2019). Herding behaviour in cryptocurrencies. Finance Research Letters, 29, 216-221.

Bouri, E., Lucey, B., & Roubaud, D. (2020). The volatility surprise of leading cryptocurrencies: Transitory and permanent linkages. Finance Research Letters, 33, 101188.

Bouri, E., Shahzad, S. J. H., & Roubaud, D. (2019). Co-explosivity in the cryptocurrency market. Finance Research Letters, 29, 178-183.

Corbet, S., Lucey, B., & Yarovaya, L. (2018). Datestamping the Bitcoin and Ethereum bubbles. Finance Research Letters, 26, 81-88.

DeFusco, A. A., Nathanson, C. G., & Zwick, E. (2022). Speculative dynamics of prices and volume. Journal of Financial Economics, 146(1), 205-229.

Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American statistical association, 74(366a), 427-431.

Dowling, M. (2022a). Fertile LAND: Pricing non-fungible tokens. Finance Research Letters, 44, 102096.

Dowling, M. (2022b). Is non-fungible token pricing driven by cryptocurrencies?. Finance Research Letters, 44, 102097.

Fisher, J. D., Geltner, D. M., & Webb, R. B. (1994). Value indices of commercial real estate: a comparison of index construction methods. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 9(2), 137-164.

Galbraith, J. K. (1954). The Great Crash: 1929 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1988 [1954].

Goetzmann, W. N., Renneboog, L., & Spaenjers, C. (2011). Art and money. American Economic Review, 101(3), 222-26.

Goldberg, M., Kugler, P., & Schär, F. (2021). The Economics of Blockchain-Based Virtual Worlds: A Hedonic Regression Model for Virtual Land. Available at SSRN 3932189.

Hill, R. J. (2013). Hedonic price indexes for residential housing: A survey, evaluation and taxonomy. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27(5), 879-914.

Liao, J., Peng, C., & Zhu, N. (2022). Extrapolative bubbles and trading volume. The Review of Financial Studies, 35(4), 1682-1722.

Moratis, G. (2021). Quantifying the spillover effect in the cryptocurrency market. Finance Research Letters, 38, 101534.

Nakavachara, V., & Saengchote, K. (2022). Does unit of account affect willingness to pay? Evidence from metaverse LAND transactions. Finance Research Letters, 49, 103089.

Pénasse, J., & Renneboog, L. (2022). Speculative trading and bubbles: Evidence from the art market. Management Science, 68(7), 4939-4963.

Philippas, D., Rjiba, H., Guesmi, K., & Goutte, S. (2019). Media attention and Bitcoin prices. Finance Research Letters, 30, 37-43.

Phillips, P. C., Shi, S., & Yu, J. (2015). Testing for multiple bubbles: Historical episodes of exuberance and collapse in the S&P 500. International economic review, 56(4), 1043-1078.

Shahzad, S. J. H., Anas, M., & Bouri, E. (2022). Price explosiveness in cryptocurrencies and Elon Musk’s tweets. Finance Research Letters, 102695.

Simpson, H. D. (1933). Real estate speculation and the depression. The American Economic Review, 23(1), 163-171.

White, E. N. (2009). Lessons from the great American real estate boom and bust of the 1920s (No. w15573). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Author:

(1) Kanis Saengchote, Chulalongkorn Business School, Chulalongkorn University, Phayathai Road, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330, Thailand. (email: [email protected]).

[8] One example of a lending platform which accepts NFTs as collateral is NFTfi, which offers loans denominated in wETH and DAI (a collateralized stablecoin). As of September 9, 2022, the majority of loans denominated in wETH are secured by Bored Ape Yacht Club and Mutant Ape Yacht Club NFTs, while loans denominated in DAI are mostly secured by wrapped Cryptopunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club. Loans collateralized by LAND NFTs account for a less than 1 percent of outstanding loans on the platform. [9] See, for example, https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=26262596, accessed on September 9, 2022.