Resisting Tipping Culture with Kotlin Multiplatform

Over the past few years, tipping culture in the U.S. has shifted in subtle but deeply felt ways. What used to be a straightforward gesture of appreciation has transformed into an obligation that feels like it’s being capitalized at every turn. I started noticing how often I’d be asked for a 20% tip for nothing other than being handed my food in a drive thru or pickup order and wondering “is this for notable service? or is it just some sort of good deed?” I’m not against tipping. I think a tip jar is an excellent opportunity to do something nice for a stranger working a service job. I honestly tip $1-2 every time I pick up fast food and always do 20-25% if I’m being waited on. But with the advent of tablets calculating and soliciting percentage tips, I felt the practice was becoming emotionally predatory. I’d notice attitude from people if I only tipped 10% on a $30 pickup order, or being handed a $60 concert hoodie. I recognize that service jobs are not easy, and maybe I’m the one that’s entitled for saying this, but I don’t feel handing someone a sweatshirt alone elicits $12, and yet, I always felt dissonant and morally compelled to do so. Apparently I wasn’t alone as 9 out of 10 of Americans say that tipping culture has gone too far. So, I came up with a crazy idea to hopefully resolve some of that conflict and do some good in the world.

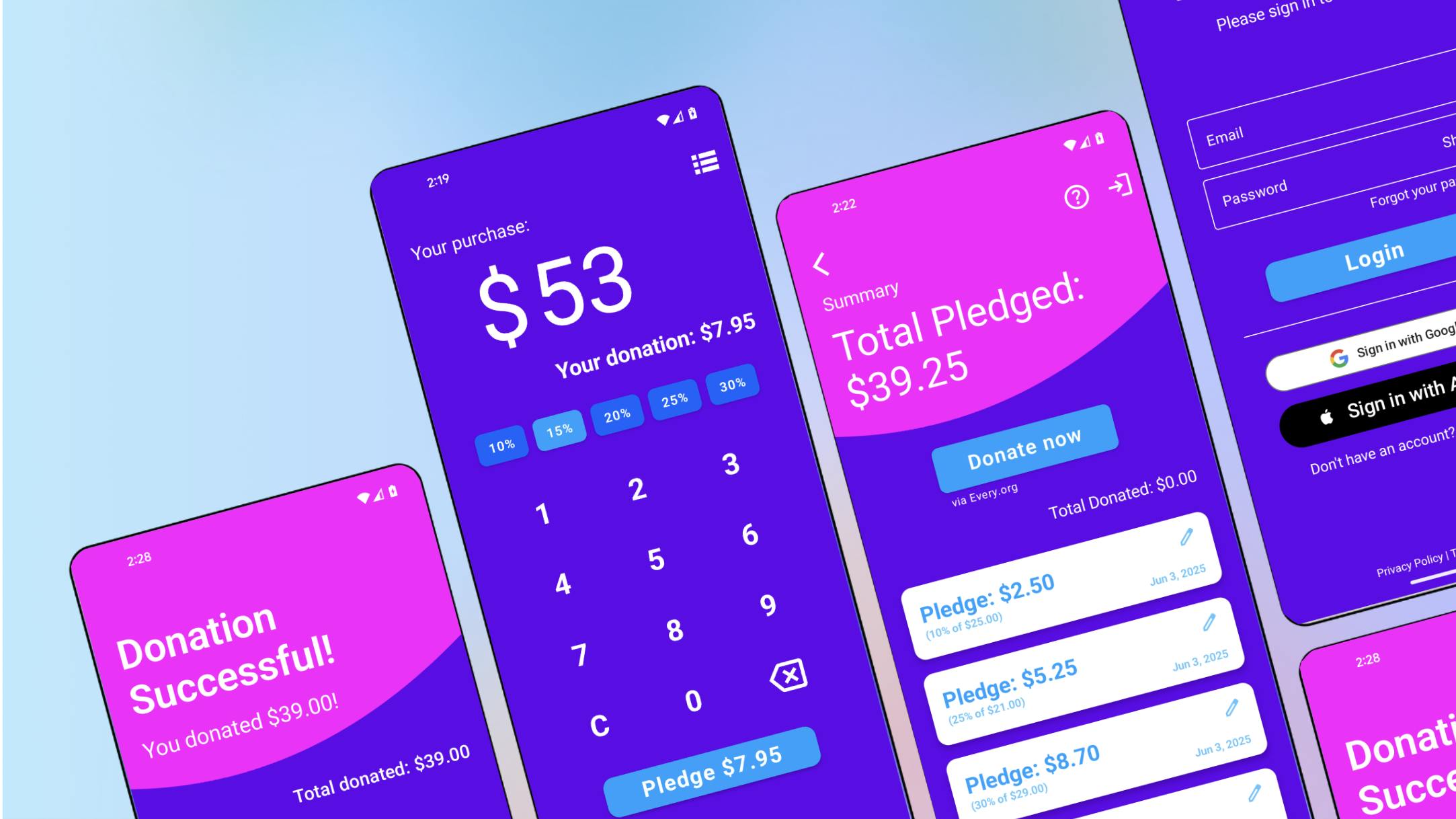

It’s called TippingPoint. It’s a free app that lets you track the tips you would have given during uncomfortably audacious tipping requests and then donate the total to charity at the end of the month. I get zero cut of it. I don’t make any money from it. It’s got no ads. It’s just a tool I thought could help solve a modern frustration and direct funding to people in extreme poverty.

The app is pretty straight forward: Put in the purchase total, click the percent you would have tipped, click “pledge”, and tip $0 irl knowing that: you’re not greedy, you’re still giving up your money, but it’s going to people in desperate need all over the world. You can then donate the sum of the money via every.org, a respected open charity API, through the app directly to UNICEF USA. The charity API takes no cut (other than an optional donation, ironically in tip form), and UNICEF USA is an extremely well-vetted charity with a very high legitimacy score, and a mission that feels universally supportable. Though, it should be stated I have no affiliation or partnership with either of these charities or platforms, it’s simply use of an open API.

The app also requires a user to donate after 30 days in order to continue using it. I don’t care if users hate that, uninstall, and 1-star the app. I wanted to keep users accountable to the mission of the app, rather than being able to stiff workers, feel good about it, but not actually follow through.

This isn’t an anti-tipping campaign. The app actually makes you agree not to use it to stiff people in effectively all traditionally tipped jobs such as servers, baristas, drivers, tattoo artists, etc. The goal wasn’t to get in the way of anyone’s livelihoods, it’s just to give people the courage to keep the recent explosion of tipping prompts from getting worse.

Tech Stack

The app was made in my spare time with a simple tech stack consisting of Kotlin Multiplatform Mobile, Compose Multiplatform, Room Multiplatform, and Firebase’s Auth, Firestore, and App check.

Platform

This was my first time working with KMM, or any multiplatform development, and it was surprisingly intuitive. Getting it building and running on android was simple, as Android Studio already has plenty of support for Kotlin and Jetpack Compose. Effectively, you just write all your code in your commonMain module with an App() composable as the access point. Your androidMain and iosMain modules then contain support for your native implementations pointing to it. AndroidMain was straightforward with general Activity/Application subclasses, while iosMain was mostly a bridge to decompile into native iOS code (another project sibling directory called iosApp). It also featured a very intuitive expect/actual function system that made distinct logic between platforms very easy.

UX

The Compose Multiplatform code was very intuitive to work with. I’m a huge fan on declarative UI which is heavily enforced by Compose’ design. I had very, very few instances of unsupported behavior featured in native android Compose, as virtually all complex animations and layouts worked great on both android and iOS. A lot of people highly criticize Compose’ performance, but I found no issues, albeit with my fairly simple layouts. Parity in performance and visuals felt perfect between the iOS and android builds, with an exception of easily remedied logic for respective status and navigation bar insets.

Persistence

Room Multiplatform also worked great across both platforms once I got it building, but there were a few minor Gradle headaches getting there. Anyone that has worked with Room on android will feel completely at home working with the multiplatform port.

Auth

Firebase was a bit of another story. There is a fantastic library for supporting Firebase on KMM by GitLive that made things very simple, however, it did not yet support Firebase App Check, a feature that guards against malicious Firebase usage barraging. This feature was critical for my app given that it was inevitably going to be fairly controversial and likely to invite attacks. Because of that, I had to scrap it and implement Firebase natively in each respective mobile platform. Android made this very easy, however, communication between the Kotlin and Swift code for the iOS side proved to be very tedious with a lot of awkward reflection-based interaction. This was the only way I could manage to do it, but honestly, probably “skill issue.” User authentication through firebase works very well with Kotlin Coroutines, and storing user functional data, such as their pledges, how much they’ve donated, etc. was easy using Firestore, albeit a bit pricy.

tl;dr

In my experience, Kotlin Multiplatform Mobile has a lot of potential, especially for simple apps, however, given the small technicalities, few missing features, and necessity to bridge implementations with the respective platforms limitations, it seems like a difficult sell as a practical option for a large commercial app for the time being, but I’m optimistic looking forward. “React Native is the future” they say…