Examining Nigeria – Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) Agreement in 2001

Similar to the previous agreements, the 2001 agreement between the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) and the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) remains a landmark document in the history of higher education reform in Nigeria. Our analyst points out that while it was born out of intense negotiations and mutual frustrations, it also offers a rich case in how complex systems are shaped by a web of relationships, interests, and compromises. To understand its impact and limitations, our analyst looks beyond the surface of policy and examines how influence, power, and negotiation shaped the final outcome.

The Power of Relationships in Shaping Policy

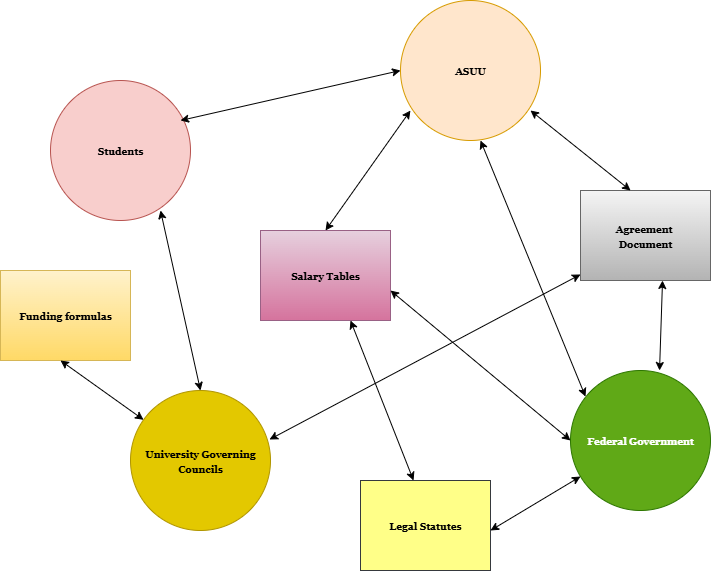

At the heart of the agreement lies a network of actors whose interests were often at odds. ASUU, representing the academic workforce, pushed for autonomy, better funding, and improved working conditions. The Federal Government, balancing national priorities and budget constraints, sought to maintain control while appeasing demands. University governing councils, students, and state governments also played indirect but important roles.

Exhibit 1: Network of actors and influence

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 18 (Sep 15 – Dec 6, 2025) today for early bird discounts. Do annual for access to Blucera.com.

Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass opens registrations.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab: From Technical Design to Deployment.

What makes this agreement compelling is how these relationships influenced the final document. ASUU’s initial proposal ran over 140 pages. In line with this, our analyst notes that writing over 100 pages proposal indicates deep frustration and a desire for systemic change. The government’s counteroffer was less than a third of that length, signaling a more cautious approach. The final agreement, somewhere in between, was not just a compromise, it was a reflection of how each party managed to assert its influence.

Documents as Tools of Negotiation

Our analysis further reveals that the agreement itself is more than a record of decisions. It is a tool that encodes the values, priorities, and power dynamics of its time. Salary tables, funding benchmarks, and governance structures are not just technical details, they are expressions of what each side believed was fair and necessary.

For example, ASUU’s insistence on a benchmark of ?200,000 per student per year was not just about money. It was a statement about the value of education and the need to reverse years of underfunding. Similarly, the push for university autonomy was about reclaiming control over academic decisions and resisting political interference.

Yet many of these proposals were met with delays or vague promises. The government deferred legal reforms to the Ministry of Justice, and implementation timelines were left open-ended. These gaps reveal how documents can be used to stall, soften, or reshape demands without outright rejection.

Unresolved Tensions and Fragile Agreements

Despite its scope, the agreement left many issues unresolved. The appointment process for university leaders remained contested. The question of tuition fees was rejected at the federal level but left open for state universities. The reinstatement of dismissed staff under military-era decrees was promised but not guaranteed.

These unresolved areas point to a deeper truth. Agreements like this are rarely final. They are snapshots of a moment in time, held together by fragile consensus. When the underlying relationships shift (due to political change, economic pressure, or public outcry) the agreement itself can unravel or be renegotiated.

Our analyst stresses that this fragility is not a failure. It is a reminder that reform is a process, not a destination. The 2001 agreement did not solve all problems, but it created a framework for continued dialogue and advocacy.

What We Can Learn Today

Over two decades later, the FGN-ASUU agreement still holds lessons for policymakers, educators, and reform advocates. It shows the importance of inclusive negotiation. When all voices are heard, especially those closest to the problem, the resulting policies are more grounded and credible.

It highlights the need for clarity and accountability. Vague promises and deferred actions weaken trust and make implementation difficult. Reform documents must be clear not only in their goals but in how those goals will be achieved. It also reminds us that documents are not passive. They shape behavior, expectations, and future negotiations. Treating them as living tools rather than static records allows us to adapt and respond to changing realities.

The 2001 agreement may not have delivered all it promised, but it remains a powerful example of how change begins, with conversation, compromise, and the courage to imagine something better.